I licked a wall once, only six blocks from here. As a child thankfully, but still.

I think I've made it clear here (although after more than a decade of prattling online, I'm no longer much inclined to fact-check my own sloppy reportage) that I am not a native Minneapolitan. I grew up all over the place, dragged around by my stepfather's alcoholic whims and the vagaries of his chosen profession: welding supplies sales.

Robert (the stepfather with Southern Comfort breath, who was neither Southern nor comforting) grew up in Minneapolis, was born here. Even so, he didn't talk about it much, or fondly, and the fact that it was his birthplace had little to do with all of us ending up in the Twin Cities. The only family he had in Minneapolis by the time he'd entered my life in his homicidal navy Rambler was his Aunt Betty, who was his mother's older sister. Betty was a true iconoclast, a real man's woman. A gameswoman, she hunted and fished and drank, played cards with her husband and his friends, never had children, and eventually outlived her husband by many years. She lived to be 103, drove a car only once (her husband Paul was attempting to teach her to drive at some point in the early 1930's, and she didn't care for his tone of voice so she never got behind the wheel of a car again. Happily, this was a story that they both loved telling, tipsily and often.)

By the time I knew Betty she was in her early seventies. She had lilac-rinsed hair, quite vivid, and the sort of doughy, crepe-y skin that feels like a powdery balloon filled with talc. She was sweet and utterly nonjudgemental, the kind of old Auntie that would slip you a tenner everytime she saw you, whispering in your ear not to tell your parents about it, because she knew they'd keep at least half for themselves. She was also very nearly deaf, and wore an extraordinarily awful hearing aid, precariously clipped to her bra. It looked like a circular microphone, about the size of a thick poker chip, and it had a curly, beige, twisted wire that wended its way up through her blouse to an unconvincingly 'flesh'-colored earpiece, huge and protuberant, that seemed to accomplish nothing whatsoever. She'd futz with 'her aid' incessantly, and it'd squeal and whistle, provoke odd hissing noises from her wrinkly bosom, and when you got close to her, you could hear your own voice echoing back tinnily and muffled, emanating from her breasts.

When she used the phone she'd hold it inverted, the mouthpiece at her mouth, the earpiece disappearing into her blouse, which was always unbuttoned to an oddly racy extent for easy access when she needed to make a volume adjustment. The first time I saw her do this I was about five, and I was equally fascinated and appalled; afterward though, whenever she'd call us long distance in Pennsylvania or Indiana or wherever, I'd become tongue-tied, freaked that I was hollering across the country into her substantial bra.

Unlike most of Robert's family, she loved my sister and me equally despite my well-known bastard status. Betty'd wanted to have kids, but there was some business about a collapsed uterus that she'd tearfully allude to when she'd downed a sufficient number of Presbyterians (her signature drink.) She loved Robert without any reproach as well, but made it clear that she knew exactly what he was about. Oddly, as warm and generous as she was with family, she could be an absolute twat to servicepeople, waitresses, cabbies and the like. I really think it was a class thing, as well as generational; she'd grown up somewhat privileged in Canada with a French nanny, and her family had several maids, although she happily spent most of her adult life in a very middle class existence.

Betty was a regular at a Chinese restaurant downtown (now sadly gone) called the Nankin. 'Regular' is a bit of an understatement: she'd proudly tell anyone that would listen that she'd not missed a weekday lunch there since the day it opened, sometime in the twenties. This was probably not exactly true, but almost nearly so, to the point where it might as well have been the case. She'd take the #4 bus down Johnson, attend a noon mass downtown, and then order the broiled walleye at the Nankin (she'd talk about someday trying the #6 (subgum chow mein) but never got around to it; on really stifling days in August, occasionally her resolve would weaken and she'd order a chicken salad sandwich, because it was 'light fare'.) She sat at the same table whenever possible, and later in life, she'd take turns snubbing a group of other old women that had each become nodding (or pointedly not-nodding on occasion) acquaintances by virtue of being seated imperiously near each other for years.

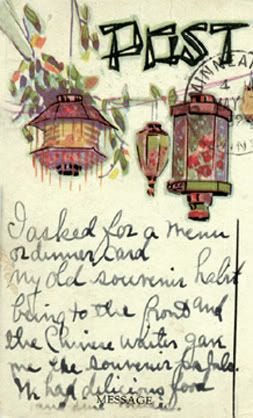

The Nankin had several incarnations (it moved three times, always within a block or so, and it had a sister restaurant- same owners, same name, in Chicago.) While in some decades the place was posh and ornate, a swanky, overdecorated near-club environment of red velvet and silk lanterns, balconies, fantail goldfish and waiters in stiff black suits, in later years, it had a Chinese-deco-luncheonette vibe, with green metal tables and chairs, stainless teapots instead of porcelain, and waiters in deep maroon mandarin jackets of poplin.

It lasted until the mid 1990's, outliving Betty handily anyhow. As a teenager, I'd pass it and marvel at the sort of loyalty (or inertia) that Betty had shown all those years, wondering what that was about, that kept someone around a place, while never really engaging in what it had to offer.

My family and I made a grueling, cross-country road trip to visit her when I was about seven years old. She lived in a Tudor fourplex apartment building, all creamy stucco and chocolate brown trim in Northeast Minneapolis, oddly enough, about six blocks from where I now live. She and her husband Paul had moved in sometime right after World War II, and she'd not budged or redecorated since. Her apartment smelled brownish, like every batch of gravy she'd ever concocted, which sounds awful, but wasn't. The place was dim, shaded in front by a massive grey pine that had been planted too close to the house and obliterated any sunlight that might have found its way in, and the houses on either side ensured that the place stayed cavelike and dusky all day. As a kid, I only saw that she had heavy draperies, as well as massive beige metal Venetian blinds, and I assumed that the place had to be crepuscular, that it was some sort of better-unmentioned elderly convention.

Generally, I found her home embarassing, excessively intimate. Besides the accumulated decades of cooking smell, there was the general girdle-beigeness of it all: it was all too reminiscent of her hearing aid, her foundation-taupe sturdy bra, her face powder. The walls in every room were swirled plaster, painted in that alkyd beige of ace bandages, the color of meringue peaks, which was peculiar since she almost always had a grasshopper or lemon meringue pie sweating on her dining room table. The place was lousy with gothic arches, including an odd little shrine-like niche in a hallway that housed, and apparently honored, a glossy black dial telephone with a cloth cord. Her bedroom was the same inundating beige, with a similarly colored satin quilt on the bed, and three identically-hued throw pillows in dupioni silk that she arranged every day after making her bed.

Because of her 'French Canadian' upbringing, Betty pronounced certain words in an oddly formal manner, audibly inserting hyphens in a way that fascinated me, pretentious little 'mo that I was: tele-phone, week-end, tele-vision (she didn't have one) all latter-syllable accented, and everything was a 'machine', as in record-playing machine, and mixing machine. She'd order chow mein (show-men) from Jung's-down-the-street (still there) and talk about how she'd always wanted to try the pizza (pronounced something like 'lizard', only without the 'rd'), from the "parlor that opened up." She was also alarmingly racist, only in a completely generational, hateless way, if that's possible. Asian people were all Chinamen, and once in a restaurant, she drunkenly and tearily carried on about a time when she was in the hospital and she saw "a little pickaninny baby minutes after it was born, and it was white as you or me, and then the color flowed into it, and it was dark as night, sweet little thing."

During our visit I tried to stay out of the way of the adults and their drinking, and I wound up sitting under her dining room table, silently drawing elaborate pictures in crayon on a stack of typing paper (Anna didn't approve of the idea of coloring books much.) Betty made dozens of unecessary trips to the kitchen and the bathroom, and on each pass she'd bend down uncomfortably and beam at me from between her lyreback chairs, surreptitiously slipping me a treat: a cookie, or a quarter, a Russell Stover chocolate. I drew a picture for her of a small dog under her dining room table, looking expectant. She laughed every time she picked it up, never revealing the private joke.

As always, after awhile my sister and I were sent outside 'to play'. I can only assume this was because Robert was hitting Betty up for money (again) and didn't want an audience. We were dispatched to Betty's stingy, narrow back yard: a concrete stoop, some small shaggy patch of grass riddled with tree roots, a clothesline, an old, weathered, mostly-wooden push-lawnmower, and a crumbly sidewalk that led back to an alley, which we'd been admonished to stay clear of. It was a different era, with no GameBoys or text messaging: what exactly our parents expected us to do when we were sent outside to play, to get some fresh air, was never clear. What was apparent though, was that we were not to be noisy, or to come back inside until we were summoned. We gave in to our natures: Mary hid, which is what she did (all throughout our childhoods: in her stuffy bedroom closet while wearing a favorite winter hat, or wrapped completely and awkwardly in a blanket, crawling invisibly [to her mind anyhow] around the perimeter of the living room when I had a birthday party, or in a field behind our house- Mary was always trying to make herself scarce.) I did what I did most as a child: I worried about what was coming next, and what I might do to make it less awful.

While Mary squirrelled in and out of the mangy autumn lilacs, working on perfect concealment, I stood back near the alley, squinting worriedly at the house, projecting the possible horrors that the ride back to the motel might entail and wondering at the same time what stucco was made of, and why there wasn't any in Pennsylvania. The house looked like a chocolate-iced shortbread cookie, the sort that are encased in chocolate on the bottom side, and drizzled similarly and decoratively on the top. Betty's building's stucco was old and dirty, and the tan edges had a dark, overbaked quality that made them even more cookie-like, as well as a sparkly mica flake that looked like sugar crystals. The general appeal was that of the sort of gingerbread houses that shopping center Santas were often housed in: sugary and warm-toned, crispy and rounded, oddly weightless. I walked toward the stoop and inspected the stucco closely, picking at some of the flakes and slowly extending my tongue to find that it tasted salty, a little sooty, and smelled marvelously of rain, in the way window screens can.

Mary had tired of being scratched by the lilacs and was standing in the center of the yard, looking up at the elm branches. I walked over to her and we both lay down on the grass, looking up at the sky through the branches. It was early autumn, this time of year precisely, and the clouds were very high and grey, and just as when the sun broke through it was uncomfortably warm and stifling, like a little fever, when it slipped back beneath the felty cover, it would feel inhospitably chilly, and damp. There was no comfort in Minneapolis, nothing that felt completely inviting exactly, and I wanted to go home, without the necessary trip that would take me there. The sparse elm branches met in the center of the yard, overlapping into more gothic arches, a vaguely ecclesiastical dome that made even the outdoors seem foreign, slightly judgemental and churchy.

It still feels that way here in Minneapolis, sometimes a little too often. I am dumbfounded that after such a nomadic childhood, one in which I spent ample time in places that felt more innately hospitable, that I remain here, and I worry that I'll end up staying out of spite, so that I can not nod at certain people, ensuring not only their indignance, but their mild retaliation. Such is the passive/aggressive mindset that Minneapolis is known for by those who arrive and then leave.

I've plotted my escape more than once, and elaborately, one time even making very public plans to move to New Orleans with Brian, until he ruined that place for me, maybe completely. I don't know what it is that keeps me here, ironically only a few blocks from where I lay that day sweating and full of childhood dread, killing time under the unkind dome of sky, against my will and better judgement, in that plain backyard, waiting to be called in.